George Gershwin the Painter

In this post, we introduce guest writer Richie Gerber. Richie has written previously about Gershwin in his book JAZZ: America’s Gift ~ From Its Birth to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue & Beyond and here shares with us some thoughts on Gershwin’s paintings.

“I noticed especially how he tried to supply to his painting the same warmth, enthusiasm and power that characterized his music.” – Henry Botkin (Armitage, 1938)

Whenever George Gershwin’s name is mentioned, without exception everyone thinks—musical genius. Few are aware that he was an exceptional painter as well. Indeed, he was one of a rare few that excelled in two completely different art forms, having gravitated to the easel in his late twenties.

Self Portrait by George Gershwin (1936): image courtesy of the Library of Congress, published with permission of the Gershwin Estates

As kids, George and his older brother, Ira, were both avid doodlers. Early on, Ira actually considered becoming a professional illustrator. An article about George Gershwin’s artistic talent entitled “A Composer’s Pictures” in the January 1934 edition of Arts & Decoration declared, “If his family had presented him with an easel and some paints when he was a child, instead of with a piano, he would be a professional painter today rather than a musician.” A May 4th 1930 write-up in New York World put the genesis of young Gershwin’s career path a bit differently, “He believes that if his public-school teacher hadn’t laughed when he showed her a drawing he had made, he would have been a very successful artist today.”

In 1927, George planned a get-out-of-the-city vacation to the country during which his brother Ira encouraged him to take up the fine art of painting. This 1927 trip quickly morphed into a brush-and-canvas country vacation, and the trip revealed Gershwin’s extraordinary artistic talents. He started with watercolors and quickly progressed to oils, and in both media he showed a high degree of skill.

George’s cousin, the modernist artist Henry Botkin, became his mentor in this newly discovered world of fine art. Under the masterful eye of cousin Bodkin, Gershwin developed into an accomplished artist in his own right, creating many oil paintings and pen-and-ink drawings, as well as watercolors. Henry, or as George called him, “my cousin, Botkin, the painter,” was a celebrated American Modernist painter and art connoisseur who graduated from the Massachusetts School of Art. Bodkin helped his younger cousin amass a world-class art collection and taught him the ins and outs of painting. Although George drew and painted landscapes and still lifes, his focus was on portraits.

In 1928, after being bitten by the painting bug, George moved out of the Brownstone he shared with his parents and three siblings on the Upper West Side and into his new art deco penthouse perched on Riverside Drive and Seventy-Fifth Street with panoramic terrace views of the mighty Hudson River. His brother, Ira, and Ira’s wife Leonore, had an adjoining duplex.

It was a high style, ultra-modern bachelor pad with a painter’s studio vibe. A 1932 article in Life, as quoted in The Gershwin Reader edited by Wyatt and Johnson, said, “A visitor…might believe, and with reason, that he was wandering by mistake into a painter’s studio as he enters the home of the man who led the jazz parade from Tin Pan Alley to Carnegie Hall. Paintings hang all over the walls. They stand on the floor, resting against tables and chairs…. An easel, upholding a half-finished portrait…occupies the center of the floor space.”

The new apartment proved perfect for the newly invented artist. George was truly “A Typical Self-Made American” (a Gershwin song from his 1927 show Strike Up The Band) and was not adverse to using his fame, fortune, music, and art to impress his guests. In fact, the May 4th, 1930, article in New York World discussed George’s artist shtick saying, “He turns every attractive female visitor into a model.”

The new apartment and painting studio became Gershwin’s sanctuary in the sky, where he would find himself absorbed at the easel for countless hours. A 1933 article titled, “George the Ingenuous”, as quoted in The Gershwin Reader, described George contemplating his future, “Spending long hours at his easel, looking up only to gaze meditatively over the rooftops of the magical city and wonder out loud whether he might not do well to give up music altogether in favor of oil and canvas.”

Gershwin owned paintings by French Fauvist-Impressionist Georges Rouault who was his favorite artist. Gershwin would often say, “If only I could put Rouault into music” ( Architectural Digest, November 1995). Henry said of his cousin George, “The work of Rouault was especially close to him and he was constantly enthralled by the life and spirit that animated his work. He wanted his own pictures and music to possess the same breathtaking power and depth” (Armitage, 1938). Botkin also made note of his cousin’s “profound and genuine talent” stating, “He [George] developed a mastery of his craft” (Armitage, 1938). After Gershwin’s untimely death, Botkin speculated, “With time his talent might have flowered into something comparable to his genius as a composer” (Armitage, 1938).

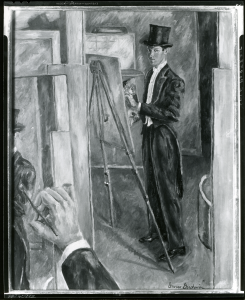

“Self Portrait with Top Hat” by George Gershwin: ©Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Photograph Archives, Smithsonian American Art Museum, published with the permission of the Gershwin Estates

As far as composing and painting were concerned, he characterized himself as a “modern romantic.” Gershwin was associated with modern composition, and his life was transformed when his signature symphonic jazz piece Rhapsody in Blue premiered at the 1924 Aeolian Hall “Experiment in Modern Music” concert. In an article he wrote for the 1930 book Revolt in the Arts, “The Composer in the Machine Age,” Gershwin clearly affirms his attraction to the modern: “The Machine Age has influenced practically everything. I do not mean only music but everything from art to finance.” Cousin Botkin connected the modernist dots between George’s music and art, writing, “If he was interested in the modern trends in art it was because they had the same qualities as the music with which he was concerned” (Armitage, 1938). Botkin also compared his cousin’s art works to another modernist, Pablo Picasso, stating that some of Gershwin’s paintings “could have been the work of Picasso” (Armitage, 1938).

Before Gershwin’s death in July 1937, he was planning a one-man show of his art. Several months after he died the exhibition opened at the Marie Harriman Gallery at 61 East 57th Street. The show ran from December 18, 1937, to January 4, 1938, and according to the gallery brochure featured 39 paintings, drawings, and watercolors.

The exhibition received critical acclaim with articles such as the December 20 Newsweek review titled “Posthumous Exhibit Shows That Gershwin Knew Harmony on Canvas Also.” The New York World Telegram, opined that Gershwin’s paintings were of “undeniable quality.” (Pollack, 2006) In a December 24 review of the exhibition, Henry McBride, The New York Sun art critic and modern art supporter, wrote that “He was not yet actually great as a painter, but that was merely because he had not yet had the time—but he was distinctly on the way to that goal. He had all the aptitudes…. If the soul be great, all the expressions emanating from that soul must be great” (Ewan, 1956).

Gershwin’s “modern romantic” soul was always searching for expression, which he found in both music and art. He started to view his music in terms of painting and was able to live and thrive in both worlds. Let’s give Gershwin the last word on art and music: “Music is design—melody is line; harmony is color…. Dissonance in music is like distortion in a painting” (Arts & Decoration, 1934).

Stay tuned for my next post on George Gershwin’s multi-million dollar art collection!

Further Readings:

Armitage, Merle. ed. George Gershwin. New York: Longmans, Green & CO, 1938.

Clarke, Gerald. “Broadway Legends: George Gershwin: The Celebrated Composer’s Manhattan Penthouse.” Architectural Digest (November 1995): 192-195 & 270.

“A Composer’s Pictures”, Arts & Decoration, January 1934.

Ewen, David. “A Journey to Greatness.” New York, 1956.

Gershwin, George. “The Composer in the Machine Age.” In Revolt in the Arts, Oliver M. Sayler ed., 1930.

Kober, Arthur. “Some Things About a Young Composer.” New York World, May 4, 1930.

Pollack, Howard. George Gershwin: His Life and Times. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Wyatt, Robert and John Andrew Johnson, The George Gershwin Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

“Posthumous Exhibit Shows That Gershwin Knew Harmony on Canvas Also.” Newsweek, Dec. 20, 1937.

Musician-Author Richie Gerber’s book JAZZ: America’s Gift ~ From Its Birth to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue & Beyond was named to Kirkus Reviews’ Best Books of 2015. For more information visit his website: https://jazzamericasgift.com

Apparently, George was more than a doodler!

I try to learn something new every day and you did it for me today. Great article.

You were right. I never knew Gershwin was an painter as well. Hard to believe Rhapsody In Blue was written almost 100 years ago. Enjoyed your article.

In November 1935 Gershwin went to Mexico and hung out with Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Isamu Noguchi, Miguel and Rosa Covarrubias, and Roberto Montenegro.

Thanks for this blog post. I am curating a large-scale museum exhibition on Gershwin as painter and art collector that will open in February 2023 in Savannah Georgia at the Telfair Museums and then tour to other venues TBD. There will also be an accompanying fully-illustrated catalogue. A fun project, and one I have been wanting to do for quite some time.