When Blue Was New

When Blue Was New: Rhapsody in Blue‘s Premiere at “An Experiment in Modern Music”

In the Roaring Twenties, American bandleader Paul Whiteman embarked on an audacious mission: to organize a classical concert of all-jazz repertoire. To do this, he commissioned a piece from a young George Gershwin, leading to the creation of one of America’s most famous musical compositions.

~Sarah Sisk is an undergraduate English major at U-M’s College of Literature, Science and the Arts. She is working with the Gershwin Initiative as an undergraduate research assistant in the university’s UROP program.

~Sarah Sisk is an undergraduate English major at U-M’s College of Literature, Science and the Arts. She is working with the Gershwin Initiative as an undergraduate research assistant in the university’s UROP program.

In the early 1920s, ragtime was out and jazz was hot, spreading through the music scene at a rapid pace. Stylistically transformative, this upstart genre of discordant melodies and brazen improvisation crept into the social grey areas of segregated America. Jazz naturally proved difficult to define. The word itself had many different spellings before the 1920s, including “jass,” “jas,” and “jaz,” and the type of music to which it referred was equally fluid.

Paul Whiteman, who would later collaborate with George Gershwin on Rhapsody in Blue, arrived on America’s popular music scene around the same time. In 1918, he abandoned a short-lived position in the strings section at the San Francisco Symphony for the more lucrative—and less respectable—job as a jazz violinist. When he was stationed near San Francisco in the last year of World War I, he conducted a U.S. Navy band, and after 1918 he formed a band of his own, the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. Whiteman quickly became one of America’s most successful and innovative bandleaders, famous for his talented and unusually large ensembles that specialized in orchestrated versions of popular music. During the 1920s, he sought to incorporate the new jazz style into his arrangements. He worked with accomplished black and white jazz artists, and the media began to refer to him as the “King of Jazz,” a name that endured throughout his career. Though some refuted this title, noting that his attempts to score and arrange jazz music contradicted the genre’s improvisational nature, his influence on contemporary musical culture was significant.

Whiteman (second from right) and his band in 1921.

Ferde Grofé at far right, seated at piano.

For many people at the turn of the decade, jazz was synonymous with low culture. It had originated in African American communities, and its harshest critics held up its often chaotic style as an example of everything that was uncivilized. Whiteman worked diligently to defend jazz’s reputation, but also saw in jazz and its musical predecessors (including ragtime and syncopated dance music) a “primitive” origin in African culture. (There are obviously some problematic racial issues in these stances, but that’s a topic best saved for another blog entry.) He also thought jazz would benefit from a cleaner, symphonic style, and he used his influence as a nationally celebrated bandleader to win the public’s approval. In his 1926 book titled, succinctly, Jazz, Whiteman wrote:

“I sincerely believe in jazz. I think it expresses the spirit of America and I feel sure it has a future—more of future than of past or present. I want to help that future pan out. Other Americans ought to be willing to give jazz a respectful hearing. If this effort of mine helps toward that end, I shall be satisfied.” – Paul Whiteman

It is important to note that Whiteman’s approach by no means defined jazz, which had already blossomed into a variety of styles. Instead, his efforts served to encourage the development of symphonic jazz and to expose the genre to a wider audience.

George Gershwin, circa 1920-30.

George Gershwin first collaborated with Whiteman in the early 1920s, when he was writing scores for revues. Gershwin was the score-writer for the George White’s Scandals show in 1922, for which Whiteman was the music director and conductor. Whiteman encouraged the inclusion of Gershwin’s jazz-inspired one-act opera, Blue Monday, into the show. Though critics responded to it with derision, and it was dropped after the first performance, this piece was musically progressive and serves as an early example of Gershwin’s tendency to integrate popular music into his compositions. Whiteman remained a supporter of Blue Monday, appreciating not only the hidden potential of the piece but that of young George.

Two years later, Whiteman’s and Gershwin’s musical careers intersected again. Whiteman was planning an all-jazz concert, which he called “An Experiment in Modern Music.” He was anxious to develop this concept in a relatively short time, in an attempt to preempt a forthcoming jazz concert of his rival, Vincent Lopez. Whiteman asked Gershwin to write a special composition for the performance. Gershwin’s piece, to be the penultimate work in a program arranged to illustrate a loosely chronological progression of jazz from its bawdy beginnings to its modern, “sophisticated” state, was one of only two of the concert’s commissioned compositions. As such, it was destined to be a focal point in the performance.

“No set plan was in my mind—no structure to which my music would conform. The rhapsody, as you see, began as a purpose, not a plan.” – George Gershwin

Gershwin’s work, Rhapsody in Blue, was written in a hurry. The tale of its composition has been somewhat obscured in the retelling, as Ryan Bañagale notes in Arranging Gershwin (2014). In one of the more titillating accounts, a distracted George Gershwin only remembered his commitment a month before the concert, having noticed one of Whiteman’s newspaper ads that included his name. Estimates of how long Gershwin took to compose Rhapsody differ from several months to a scant ten days. Nevertheless, the piece was still in an experimental stage of completion at the time of its premiere. Whiteman’s chief arranger, Ferde Grofé, realized the piece from Gershwin’s sketch score to suit the unconventionally large, almost orchestra-sized band. The work’s significant piano solo was incomplete in this hasty arrangement. George Gershwin himself was to perform with Whiteman’s band as lead pianist, so they left him to improvise these sections. At one point, a full page of blank sheet music was inserted in place of a piano solo, with a note for the conductor to “wait for [Gershwin’s] nod”– when George would signal the band at the end of his solo.

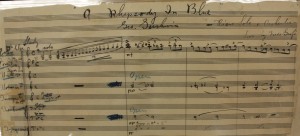

The opening measures from the original arrangement of Rhapsody in Blue, in Ferde Grofé’s hand.

Posted with permission of the Gershwin Family Estates.

Held at the Music Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Ira Gershwin had some creative involvement with Rhapsody as well, providing encouragement and counsel for his younger brother as he pieced together the composition’s tunes. Ira also contributed to the naming of the piece: when George considered “American Rhapsody” as a potential title, Ira was inspired (possibly by the musical coloring of contemporary art titles, such as James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Blue and Silver), to recommend Rhapsody in Blue instead.

“It was a strange audience out in front. Vaudevillians, concert managers come to have a look at the novelty, Tin Pan Alleyites, composers, symphony and opera stars, flappers, cake-eaters, all mixed up higgledy-piggledy.” –Paul Whiteman

“An Experiment in Modern Music” was held in Aeolian Hall in Manhattan on February 12, 1924. Whiteman’s publicity tactics had drawn a large and expectant crowd. The atmosphere was a hubbub of anticipation, causing nervousness on both Whiteman’s and Gershwin’s part. Even Ira Gershwin felt the excitement as he sat in the audience and scribbled distractedly on a program. In the end, though, their efforts paid off. While the concert’s material was neither restrained enough for the genre’s detractors nor truly “jazz” to its admirers, the event was, overall, a popular and critical success. Whiteman had succeeded: every single number received generous applause, and critics for once left positive reviews about jazz music.

As for Rhapsody, its success eclipsed that of the event. The piece was the pinnacle of the jazz-filled evening, captivating audiences with its imaginative transitions between playful discord and straining beauty. Performed in its raw early condition (which had been tweaked right up to and during its premiere), it effectively channeled jazz’s improvisational charm, encapsulating the chaotic harmonies and blue notes that would prove to electrify both the genre and the composition. Grofé later provided a smoother, cleaner orchestration of Rhapsody for a larger and more traditionally sized orchestra, but the original arrangement retains a spontaneity that makes it, for many, a favored version.

The success of “An Experiment in Modern Music” encouraged Whiteman to give more performances along the same vein. Whiteman’s established celebrity in the music industry drew crowds, and his publicity skills in turn gave Rhapsody a wide exposure. In 1924, Gershwin even recorded the work with Whiteman’s band, though gradually the two began to have differences of opinion about the proper treatment of the piece. Like Whiteman’s ideas about jazz, Rhapsody was by no means a definitive example of jazz in the Jazz Age. Still, it was a culturally significant achievement and most certainly a critical milestone in Gershwin’s career. It accomplished what the composer longed to do: combine the vibrancy of popular music with the luxurious, thematic depth of symphonic music. With Rhapsody, Gershwin had found his stride. At once earthy and transcendent, his music was destined to become as popular as jazz itself.

1924 recording of Rhapsody in Blue with the composer at the piano.

The critical edition of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924) is currently underway, lead by Dr. Ryan Bañagale. The Reno Philharmonic will be presenting a test performance of this edition on February 21st, 2016, under the direction of Maestro Laura Jackson, at the Pioneer Center for Performing Arts in Reno, Nevada.

Further Reading:

Bañagale, Ryan R. Arranging Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue and the Creation of an American Icon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Berrett, Joshua. Louis Armstrong and Paul Whiteman: Two Kings of Jazz. New Haven And London: Yale University Press, 2004.

Feinstein, Michael. The Gershwins and Me: A Personal History in Twelve Songs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Jablonski, Edward, and Lawrence D. Stewart. The Gershwin Years: George and Ira. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Pollack, Howard. George Gershwin: His Life and Work. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006.

Whiteman, Paul, and Mary Margaret McBride. Jazz. New York: Arno Press, 1974.

Hello all, here every one is sharing such familiarity, thus it’s nice to read this weblog, and I used to visit this weblog every day.

Who is the girl at the piano in the first frame to George’s left? I am guessing it is George and Ira’s sister Frances. Probably it is not Ramona Davies.

Hi Louis, The woman seated is Dana Suesse (seen in the last link to a YouTube video). She is a fascinating composer, lyricist, and musician who some hailed as “the female Gershwin”. The photo was taken at Carnegie Hall in 1932, when Whiteman’s band performed her Concerto in Three Rhythms. Here’s a link to the Digital Library at the University of Missouri where a copy of the picture is held. Thank you for your comment!