1929 Gershwin Taxi Horn Photo Clarifies Mystery

Composer George Gershwin (left) and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra percussionist James Rosenberg holding the four taxi horns used in the orchestra’s March 1 & 2, 1929 performances of An American in Paris. Photo courtesy of Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts.

A photo uncovered in the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Archive sheds a revealing light on the question of what pitches composer George Gershwin intended to be used for his iconic taxi horn passages in the symphonic tone poem An American in Paris (1928). As described in an article by Michael Cooper in The New York Times as well as on NPR’s All Things Considered, the forthcoming George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition of An American in Paris suggests that the traditional realization of the iconic taxi horn parts used by orchestras today is incorrect. Rather than sounding the pitches A, B, C, and D, I argue that the correct pitches are captured on a Feb. 4, 1929 Victor Recording supervised by the composer and should be Ab and Bb (above middle C), high D (a third above that) and low A (a third below middle C).

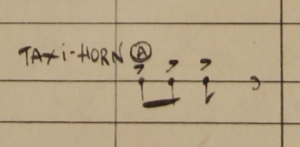

Gershwin’s handwritten notation for the first appearance of a taxi horn in measure 30 of An American in Paris. Courtesy George Gershwin Family Trusts.

At issue is the composer’s ambiguous notation in which a single-line of music notation instructs one of the orchestra’s percussionists to sound each taxi horn blast. While clearly indicating rhythm, the notation does not use a full 5-line staff that indicates pitch. Instead a circled letter identifies which of the four taxi horns George purchased in Paris is to be used. The letters used are A, B, C, & D. The composer offers no explanation of the notation in his handwritten or published scores and musicians since at least the 1930s have assumed that the letters indicate the sounding musical pitches (as if on a piano and thus forming the first four notes of an A-minor scale). I think instead that George simply labeled his four souvenir horns with a letter and handed them to the performers for the New York Philharmonic premier and subsequent Cincinnati Symphony performances with the simple instructions — when the score says “A” play that first one labeled A, when the score says “D,” play the fourth one labeled D. Unfortunately, George’s original taxi horns have been lost and the composer left no description of the pitches, at least nothing that has yet been found, before his death at the age of 38.

Snapped in the same month the Victor recording was made, the February 1929 photo depicts composer George Gershwin at left with Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra percussionist James Rosenberg, who played the taxi horns for the orchestra’s performance of An American in Paris. The taxi horns shown, especially the small and large horns, are fully consistent with the pitches heard on the 1929 recording and contradict the traditional A, B, C, D pitch sequence.

When squeezed, taxi horns sound only a single inflexible tone and this pitch is generally proportional to instrument size (with adjustments for tuning the metal reed of the horn). If the composer’s A, B, C, D notations of the taxi horn part were meant to indicate pitches A through D, the taxi horns should be in a gradual sequence of size from large to small. Instead they are both too varied in size and in the wrong order.

Gershwin taxi horns showing label and pitch as identified by editor Mark Clague as consistent with the new critical edition. Labels indicated in Gershwin’s score are given in blue; resulting pitches heard on the 1929 recording are in red.

The horns depicted in the photograph support a preference for the 1929 recording’s pitches in that two horns are of similar size, one is significantly smaller, and a fourth is dramatically larger. This is consistent with the interpretation of Gershwin’s alphabet notation not as pitch names, but as simple labels for the sequence of taxi horns to be used by the percussionist. In this case the two horns of similar size would have sounded Ab and Bb which are adjacent steps on the musical scale. The small horn would sound the high D, and the unusually large horn would sound the low A.

The ordering of the horns is also revealing. The taxi horns are secured to a wooden board and (if read from the player’s left to right) are placed in the precise ordering of medium large, medium small, small, and very large that would sound the same Ab, Bb, high D, low A pitches heard on the 1929 recording. This precisely matches the sequence of labels (A, B, C, & D) given in the score. It suggests that Gershwin took care to mount the taxi horns to reduce the chances that a percussionist would make an error sounding the unusual effect.

Mystery solved? It would seem both that the horns depicted confirm the sequence of pitches heard on the 1929 recording, and—maybe more importantly—that they unequivocally affirm that the alphabet notation names did not indicate pitch.

More information:

6 Comments